In January and February of this year, the administration announced new policies for asylum seekers arriving at the U.S.-Mexico border. Central to these policies is the increased use of a flawed smartphone app, CBP One, which is creating language, technical, and financial barriers that violate international and domestic law regarding the basic human right to seek asylum.

The government now requires Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans to use the app to apply to receive entry into the U.S. on parole. The app also is the main method for asylum seekers to make appointments for interviews about their requests to enter the U.S. under an exemption to Title 42—the law that has been used to expel potential asylum-seekers.

Additionally, in March, the administration published a proposed new rule that – if adopted – would make CBP One a necessity for those seeking asylum after Title 42 restrictions are lifted, perhaps as early as mid-May. The new rule would require the use of CBP One by asylum seekers who travel to the U.S. and pass through a third country—like Mexico or Guatemala—without seeking asylum in that third country. These migrants would have to use CBP One to make an appointment for processing at ports of entry in order to remain eligible for asylum.

Errors, crashes, and bias

While information technology has the potential to make border processing more efficient, CBP One is riddled with problems, according to a letter sent recently by 35 members of Congress to Department of U.S. Department of Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas. The app’s flaws, coupled with the inadequate number of available appointments, are keeping thousands in harm’s way in border towns in Mexico. Additionally, it is effectively creating a system that discriminates against the most vulnerable asylum seekers who do not own smartphones or do not have access to electricity or an internet connection or do not speak English, Spanish, or Haitian Creole, the only languages in which the app is available.

Users have also frequently reported technical flaws with the app itself, including persistent error messages, difficulty in uploading documents, and frequent crashes. In its current iteration, CBP One’s photo function disproportionately rejects people with darker skin tones. One of the first steps applicants must take to submit their information is to take a selfie using CBP One, but the app has trouble capturing the photos of people with darker skin tones. Repeated rejections of photos can make it impossible to complete the process for obtaining an appointment.

Compounding this cruel situation is the tech-savviness required to navigate CBP One. For example, users must first create an account with Login.gov in order to access the app, and they must also use two-step authentication to sign in once an account has been created. The manual on the app is 73 pages long. Many asylum seekers may not yet have had occasion to acquire the facility with smartphone technology that is required to use this app.

Yet another high hurdle for families trying to stay together

Even more problematic is the de facto privileging of single adults. The current process for submitting information and scheduling appointments in CBP One makes it all but impossible for a family to get a block of appointments together; each family member must book an appointment, and appointment blocks are not set aside for families. This heightens the risk of families becoming separated at the border.

Now NGOs must also serve as “Geek Squads”

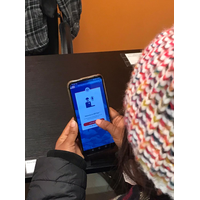

Staff in frontline nonprofits that serve refugees and asylum seekers are trying to help. The Kino Border Initiative (KBI), which provides humanitarian aid to migrants in Nogales, now holds workshops four times a week to help people grapple with CBP One.

“Most of the people we see are fleeing violence, and they’ve completed a dangerous journey to the border often marked by even more violence and trauma,” said Gia Del Pino, KBI’s director of Communications. “And now they have to tinker around with a smartphone – even though they may never have owned one or had a need for an email address.”

Those who do have smartphones face another barrier: the appallingly inadequate number of CBP appointments available at the border. According to Del Pino, there are only 40 appointments available in Nogales per day, and thousands of desperate migrants must use CBP One to vie for those appointments every day.

How you can help

“The first and foremost need is for smartphones that meet the requirements of CBP One,” said Del Pino. “Not only is a phone or tablet necessary, but it must be new enough to meet the operating-system requirements of CBP One.”

That means Apple iPhones or iPads running IOS 15.2 or later or Android phones or tablets capable of running the operating system 7.0 or newer. All devices must have at least 2GB of RAM and 16GB of storage.

If you would like to donate a smartphone or tablet, you can send it to Kino Border Initiative, 81 N. Terrace Ave, Nogales AZ, 85621.

You can also volunteer and/or make a financial donation to KBI.

Del Pino also urges RPCVs to contact their members of Congress to call for the discontinuation of CBP One’s use until all of the technical issues and inequities are addressed. An excellent example of a letter on this topic is the one written by Senator Ed Markey (D, Mass.) to the Department of Homeland Security. The “use of the CBP One app raises troubling issues of inequitable access to — and impermissible limits on — asylum, and has been plagued by significant technical problems and privacy concerns,” Senator Markey wrote. “Rather than mandating use of an app that is inaccessible to many migrants, and violates both their privacy and international law, DHS should instead implement a compassionate, lawful, and human rights centered approach for those seeking asylum in the United States.”

Article written by Cynthia Pulham Wolfe, cynthia.pcc4r@gmail.com